Your Answer Is Partially Correct Try Again H2c  C  H H2c  C  H

ABSTRACT

Open innovation (OI) practices and intellectual uppercase (IC), though from developed countries and large firms' perspective, are related to higher innovative functioning. But the influence of OI paradigm on IC and consequently on firms' innovative performance in the context of developing countries is not yet sufficiently explored. This study examined the link between OI practice and IC and their influence on the firms' innovative performance using a survey data of 243 manufacturing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) operating in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. Fractional To the lowest degree Squares (PLS) approach was applied to explore the relationships and examination the mediating part of intellectual capital. The research findings indicated that OI practise has a positive and meaning impact on intellectual capital letter and innovative operation in SMEs. Information technology as well revealed that human and organizational capitals have a meaning positive result on the innovative functioning of SMEs. Moreover, the finding showed that only human capital mediates the positive influence of OI practice on the innovative performance. Managers/owners should piece of work to improve the OI exercise and intellectual capital simultaneously to broaden the innovative performance of SMEs.

Primal words: Innovative performance, intellectual capital letter, open innovation practice, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

INTRODUCTION

In the globalized and dynamic concern settings, open up innovation (OI) is anticipated to exist one of the emerging future paradigms for managing innovation activities. In this paradigm, the internal and external ideas and paths are considered equally vital for the commercialization of innovation activities (Chesbrough, 2003; Lee et al., 2010). Recently, the subject has received an increasing attention from researchers, practitioners and governmental bodies. However, prior studies on open innovation focused primarily on high-tech and large enterprises. Currently, few studies have analyzed OI practice in the context of SMEs focusing on the differences of OI practices in small and large firms (Lee et al., 2010; Spithoven et al., 2013; Popa, Soto-Acosta

and Martinez-Conesa, 2017). Niggling attention is given to the connexion between OI exercise and performance of SMEs (Hailekiros et al., 2016; Popa et al., 2017). In addition, most of the studies on OI are descriptive by nature and based on case studies, and in-depth interviews of large and high- tech enterprises operating in developed countries (Chesbrough, 2003; Lee et al., 2010; Popa et al., 2017).

Furthermore, the human relationship betwixt OI and related management paradigms such every bit cognition direction which could bring synergy to firms' management solutions is not well explored (Užienė, 2015). Intellectual capital is ane of the fundamental knowledge management theories determined in transforming tangible resources into intangible assets. It deals with strategic direction and has a close link with innovation activities (Kohl et al., 2015). The association amid intellectual uppercase, OI practice, and innovation capabilities is witnessed in various contexts (Fan and Lee, 2009; Laine and Laine, 2012; Kohl et al., 2015). However, comprehensive researches on the effect of OI exercise on intellectual capital and after innovative performance in SMEs are meager (Užienė, 2015). Additionally, in that location are yet inquiry gaps in the literature about the effect of intellectual capital (Shih et al., 2010; Mention, 2012) and OI exercise (Popa et al., 2017) on the innovative operation of SMEs. The gap is even huge when information technology is assessed from the developing countries' perspectives (Spithoven et al., 2013; Khalique and Bontis, 2015; Hailekiros et al., 2016).

Therefore, empirical report on the bear on of OI practices on intellectual upper-case letter and consequently innovative operation of SMEs in general and specifically in developing countries is imperative (Užienė, 2015; Hailekiros et al., 2016). A research model was developed based on literature from open innovation, intellectual capital letter, and innovative operation to written report the relationship between OI practice and intellectual capital and their influence on the innovative performance of SMEs operating in Ethiopia- a developing country. The paper has important contributions. Commencement, previous studies on OI practices and intellectual capital letter were focused primarily on high-tech and large enterprises in advanced economies (Lee et al., 2010; Hung and Chiang, 2010; Spithoven et al., 2013; Popa et al., 2017). Hence this paper provides bear witness from SMEs operating in a developing land. Likewise, the extant literature on OI practice withal relies, predominantly on case studies and conceptual frameworks (Lee et al., 2010; Popa et al., 2017). The paper further delivers empirical based research findings from the context of SMEs. Finally, the paper throws light on the mediation role of intellectual capital on the relationship between open up innovation practices and innovative performance of SMEs. The remaining sections of the study are organized into literature review and hypotheses development, inquiry methodology, and assay, and finally discussion and conclusion.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

The impact of open innovation practice on innovative performance in SMEs

Firms had been using the enquiry and evolution (R&D) equally a key facility to detect, develop and finally commercialize innovations in the closed model (Chesbrough, 2003). Simply globalization and fast advancing it take changed the innovation milieu (Wang and Zhou, 2012). The availability and mobility of knowledgeable workers have increased largely, venture capital becomes abundant and knowledge is widely dispersed across multiple organizations. Enterprises are forced to motion to the OI models to efficiently and effectively utilize the internal and external resources, larn knowledge and exploit the technologies (Chesbrough, 2003). OI practice is similarly a common inclination to SMEs (Lichtenthaler, 2008; Van et al., 2009). They try to survive the astringent contest and attain their sustainable and competitive advantages through innovation. Nonetheless, high level inherent chance, dubiousness, and complexity of innovation process (Koufteros et al., 2005), limited resources (Dahlandera and Gann, 2010; Lee et al., 2010), lack of multidisciplinary competence base (Bianchi et al., 2010), low arresting chapters (Wang and Zhou, 2012) and other relevant challenges may restrict their innovative competitiveness. Too, the mobility of skilled workers, the availability of abundant venture upper-case letter, widely distributed knowledge and very brusk product life cycles brand the isolated innovation infeasible (Chesbrough, 2003). Hence, many and broad companies both large and small are practicing and increasingly adopting OI to complement their inadequacies (Van de Vrande et al., 2009; Parida et al., 2012; Hailekiros et al., 2016).

Indeed, SMEs are faced with limited resource, skills and capabilities in manufacturing, distribution, marketing, R&D funding, and structural innovation processes which are indispensable for transforming inventions into innovations (Lichtenthaler, 2008; Leiponen and Helfat, 2010). However, they are ordinarily flexible and specific (Lee et al., 2010), high-risk takers, with more specialized knowledge and proactive for market place changes (Parida et al., 2012). These factors favor SMEs to better do good from OI practices compared with their larger counterparts. In this regard, the entering, outbound and coupled OI processes (Gassmann et al., 2010; Spithoven et al., 2013; Hailekiros et al., 2016) are possible paths towards opening for SMEs. While the inbound open innovation procedure deals with searching for external ideas and data for complementing, strengthening the in-firm R&D activities, outbound focuses on uncovering the procedure of commercializing the unexploited internal innovation activities. The coupled OI combines both processes centered on strategic alliances (Spithoven et al., 2013). These processes are vital for SMEs to fill their technological, resource and competency gaps (Lichtenthaler, 2008), increase the speed and quality of innovations (Van de Vrande et al., 2009) and reply to market place changes and thereby create new channels (Van de Vrande et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010).

The inbound, outbound and coupled OI practices and their combination are possible choices firms adopt to overcome their deficiency and build up competitive and sustainable advantages from the internal and external resource. Nonetheless, the inherent high price of patent management (Spithoven et al., 2013) and the inadequate capabilities to institute balanced relationships with established firms (Narula, 2004; Minshall et al., 2010) limit the regular adoptions of outbound and coupled OI in SMEs. Hence, the OI practice in SMEs opts more towards the inbound way (Van de Vrande et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010). Considering the tendency and the bodily practices of the SMEs at mitt, the focus of this paper is on the inbound open innovation practices.

SMEs have restricted resources, they accept to search for possible ways that compensate their constraint and minimize production cost, effectively market their products and provide satisfactory support services (Lee et al., 2010). They take to formally or informally necktie with other organizations and institutions (Bigliardi et al., 2012). These connections are disquisitional for them to access new ideas, noesis, complementarity resources from the external environment and opportunity to commercialize on the shelf innovations (Dahlandera and Gann, 2010). Moreover, it aids them to get an additional resource on existing or new markets through the competencies and resources of external partners (Mortara and Minshall, 2011) and new opportunities and market channels (Buganza and Verganti, 2009). Thus, the following hypothesis is established.

Hypothesis 1: OI practice has a positive and significant effect on the innovative functioning of SMEs.

Intellectual capital and innovative functioning of SMEs

Intellectual uppercase is all the knowledge of an arrangement that is used to leverage conducting concern to achieve competitive advantages (Youndt et al., 2004; Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). In this knowledge-based and competitive era, the intellectual upper-case letter is accepted as the dominant cistron for the realization of organizations and countries' economic growth (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005; Alpkan et al., 2010; Khalique and Bontis, 2015). Information technology is also condign the unique competence gene for firms 'innovativeness (Zerenler et al., 2008). Consequent with this Tovstiga and Tulugurova (2007) pointed out that the intellectual capital is the most powerful resource to increase the performance of organizations.

Previous researchers classified IC as man, organizational and social capitals based on how knowledge is developed, accumulated and distributed (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). Human upper-case letter is the tacit and explicit individual noesis possessed by employees and shared with their organizations to create values. It includes the employees' experiences, abilities, learning or creation abilities (Youndt et al., 2004) and can be enriched past preparation and formal education (Dakhli and De Clercq, 2004). It is useful to conduct firms' activities to change their action and raise growth (Delgado-Verde et al., 2016). The social majuscule is the knowledge rooted in and amid networks of interrelationships. It is bachelor and utilized through the network (Freel, 2000). Information technology is the relational noesis from stakeholders' ties including customers, suppliers, competitors, universities and the firm'southward internal surround. It represents a valuable knowledge source to accomplish activities efficiently (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). Finally, the organizational capital represents the codified and institutionalized noesis and feel residing in and utilized through the system's repository like databases, manuals, patents processes and the like (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005; Carmona-Lavado, Cuevas-Rodríguez, and Cabello-Medin, 2010).

Basically, the IC components are closely intertwined and mutually dependent (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). Highly skilled and experienced employees use their noesis base to analyze and solve client problems (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). This process facilitates attempts to exchange and share data to learn customer preferences in a sustained fashion (Hsu and Fang, 2009), which in turn promotes the exchange and utilization of valuable information between internal professionals and external consumers. This again enhances the generation of innovative ideas that answer to customer preferences (Chen et al., 2014). Accordingly, the knowledge and skills from human uppercase embedded in new service or product evolution are expected to contribute positively to social majuscule. Contrasting the human uppercase, organizational upper-case letter is embedded in organizations infrastructure rather than in employees' minds (Chen et al., 2014; Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). This gives firms competitive advantages in advancing their collection of cognition from customers and understanding customers' needs and preferences (Chen et al., 2014). When firms sustain a adept human relationship with customers and business partners, it creates a conducive environment for their employees to discuss concern ideas, processes and innovations with customers and business organization partners thereby updating the structural capital letter of the companies (Hsu and Fang, 2009). Similarly, when employees involve in knowledge-based discussions, they would exchange their noesis with colleagues. This knowledge menstruum would upsurge the importance of the existing cognition every bit expanded knowledge becomes valuable and meaningful. The organizational capital is a mechanism to take advantage of the data and cognition. Similarly, it is a mechanism to capture, store, retrieve and communicate the knowledge and information (Chen et al., 2014).

Hence, the employees' skills and knowledge, experiences, attitudes, and commitments supported by the required infrastructure and harmonized and loyal relationship with strategic partners and customers create encouraging environments to develop distinctive competency. This distinctive competence can enhance a business firm's effectiveness, efficiency, and innovation (Zerenler et al., 2008). It, consecutively, allows firms to provide meliorate values and benefits for customers than the competitors (Loma and Jones, 2001). When a firm has a unique competency, it can attain a higher innovative performance (Garcia and Calantone, 2002). Consequently, the following hypotheses are formulated.

Hypothesis 2a: Human capital has a positive and significant upshot on innovative performance in SMEs.

Hypothesis 2b: Social upper-case letter has a positive and significant upshot on innovative performance in SMEs.

Hypothesis 2c: Organizational capital letter has a positive and significant effect on innovative functioning in SMEs.

Open innovation exercise and intellectual capital letter

The knowledge inflows and outflows from the diverse knowledge sources like universities, customers, competitors and the like positively influence the knowledge stock of the firm through organizational learning (Laine and Laine, 2012). Similarly, the inter- organizational cognition substitution is crucial for creating organizational new knowledge (Fan and Lee, 2009). Thus, considering intellectual uppercase equally a parcel of organizational noesis, increasing knowledge flows across organizational boundaries triggered past OI paradigm changes the content and level of knowledge stock in organizations. Notwithstanding, the level and means of the result of OI do on the intellectual majuscule components are anticipated to be different based on their type and nature. The OI practice establishes new partnerships and the social majuscule tends to aggrandize and becomes more diverse. The increased inter-organizational cognition exchanges caused by the opening likewise changes substantially the landscape of human capital by diversifying the knowledge borrowing and lending dimensions (Užienė, 2015). Furthermore, as the organizational value creation schemes get beyond organizational boundaries the relational capital acquires a matrix form nether this paradigm. Hence, organizations could access the systems shared by partners and could go the reward from these in joint value creation processes and increase the organizational majuscule. Appropriately:

Hypothesis 3a: Open innovation do has a positive and significant effect on social capital in SMEs.

Hypothesis 3b: Open innovation do has a positive and meaning outcome on man majuscule in SMEs.

Hypothesis 3c: Open up innovation practice has a positive and significant outcome on organizational majuscule in SMEs.

The mediating part of intellectual capital

The open up innovation practice promotes opening up firms boundaries to allow the flow of cognition in and out and advances firms' innovativeness (Chesbrough, 2003). This knowledge catamenia is as well a critical factor for organizational knowledge cosmos which in turn increases a visitor'due south innovation abilities and competitive advantage (Fan and Lee, 2009). Consequently, the positive impact of OI do on innovation performance and competitiveness can be enhanced by increasing the knowledge stock (Intellectual capital). Hence, the following hypotheses are claimed.

Hypothesis 4a: Man upper-case letter mediates the positive upshot of open innovation on innovative performance in SMEs.

Hypothesis 4b: Organizational uppercase mediates the positive effect of open i nnovation on innovative performance in SMEs.

Hypothesis 4c: Social capital mediates the positive effect of open up innovation on innovative performance in SMEs.

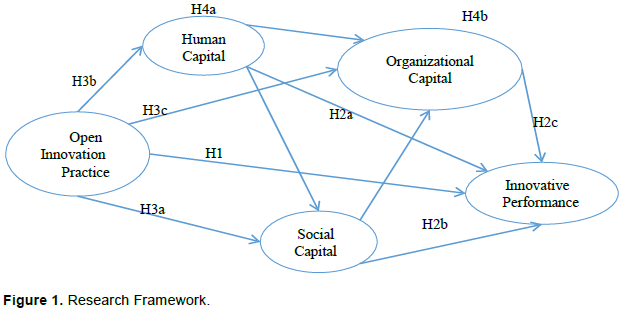

Synthesizing these word and hypotheses claimed, a research framework that describes the connections among open innovation, intellectual majuscule, and innovative performance in SMEs is formulated (Figure 1).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Sample and information collection

A survey was conducted from 08/2017 to 02/2018 to collect the data used to explore the effect of open innovation on intellectual capital and consequently innovative performance in SMEs. The survey questions were designed to assess the OI do, intellectual capital, and innovative performances of SMEs. The initial survey draft was discussed with the firms' owners, managers, and relevant governmental agency representatives. Information technology was pre-tested using 2 pilot interviews to bank check if the wording, comprehensibility, and sequencing of questions were acceptable.

SMEs relevant to the study were starting time screened from the master database in consultation with the representatives from the SMEs agents. The firms for the survey were then randomly selected from manufacturing firms comprising the metalwork, woodwork, material and garment, leather, metal, and woodwork enterprises operating in the Northern role of Ethiopia. Because the representativeness of the sector and zones covered in the study, four hundred firms were selected. The questionnaire was offset given to each interviewee and the questions were asked face-to-face in the same order. 243 interviews were correctly and successfully performed, leading to a response charge per unit of lx.75%.

The respondents who completed the questionnaire were mostly the owners every bit well equally managers of the firms (92.6%), and managers simply not owners (7.4%). The respondents were selected from the sectors (metalwork = 26.five%; woodwork = 23%; textile and garment = 26.5%; leather = 2%; metallic and woodwork = 23.5%). Furthermore, the firm's operational age ranges from four to 23 years. The information were beginning screened and SmartPLS was applied for evaluating the model and testing the hypotheses.

Measurement of constructs

The measurement scales for the constructs were established based on existing academic literature and operational definitions. Accordingly, the OI practice measurement calibration was adult based on concepts from (Laursen and Salter, 2006; Spithoven et al., 2013; Ahn et al., 2015). 8 items measurement scale was used to appraise how the linkages with partners do good SMEs. A five-point Likert- scale (ranging from one= less of import to 5= very important) was adopted to measure the parameters. The measures for human uppercase assessed the overall expertise, skill, and knowledge of an arrangement's employees. Likewise, measuring items for social uppercase assessed the system's ability to exchange and leverage within and amidst networks of employees, customers, suppliers, and alliance partners. The organizational capital measures the ability of the organizations to accordingly shop knowledge in concrete organization- level repositories. A five, five, and 4 items measurement scales were adopted from (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005) to assess the human being, social and organizational capitals, respectively. A 5-signal

Likert- calibration from ane(strongly disagree) to 5(strongly agree) was applied to measure the parameters. Finally, the innovative performance was measured with seven items scales used by (Gunday et al., 2011). Similarly, a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (much worse performance than competitors) to 5 (much better operation than competitors) was practical to evaluate the innovative performance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

SmartPLS- SEM version three.0 was used equally a data assay tool. It is a second generation tool which applies a component-based approach to SEM (Hair et al., 2016). It uses a two-footstep process to separately assess the measurement and the structural models. The start step, the measurement model, evaluates the validity and reliability of the scales. The second step, structural model, evaluates the research model and the paths amid the research constructs.

Measurement model evaluation

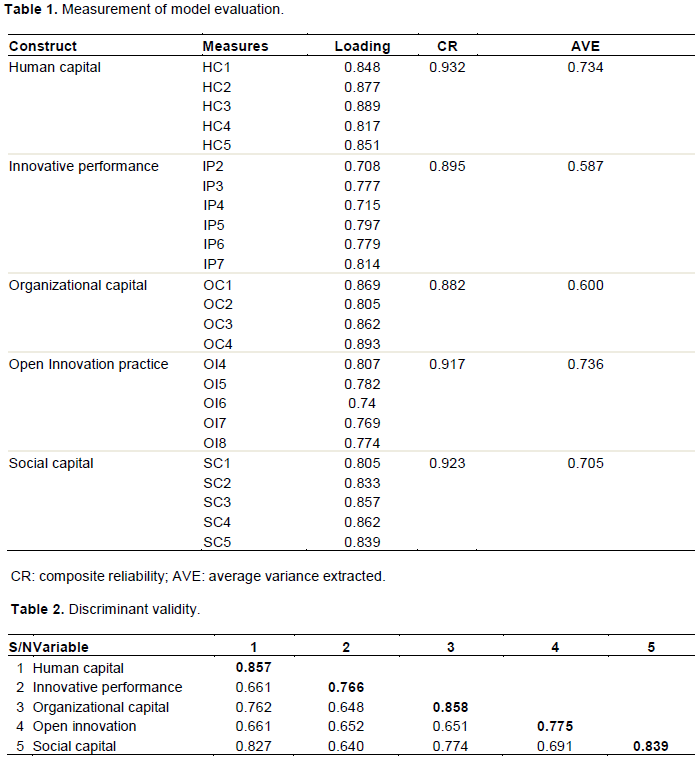

Every bit the measures are all reflective the individual itemand construct reliability, the convergent and discriminant validity of all items should be studied to examine the measurement model. The cistron loadings, blended reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to assess particular reliability, construct reliability and convergence validity respectively equally recommended by (Pilus et al., 2016). The minimum cutoff values are gear up at 0.7, 0.vii and 0.five for factor loadings, CR, and AVE respectively. To achieve the loading cutoff bespeak, iii items from OI exercise construct and i detail from innovative performance construct which did not attain this value was dropped to maintain parsimony (Pilus et al., 2016) Finally, equally it is shown in Table i the factor loading, CR, and AVE values are all higher up the suggested thresholds. Hence the items measurement reliability, internal consistency reliability, and convergent validity are satisfactory and sufficient.

Lastly, discriminant validity was assessed through the Fornell and Larcker (1981), which states that each latent construct's AVE should be greater than the construct'due south highest squared correlation of another latent construct. Table 2 shows that the correlation matrix of the constructs and the square roots of AVE (diagonal and bold). The diagonal values are all larger than the off-diagonal values in the corresponding rows and columns, signifying adequate discriminant validity.

Structural model evaluation

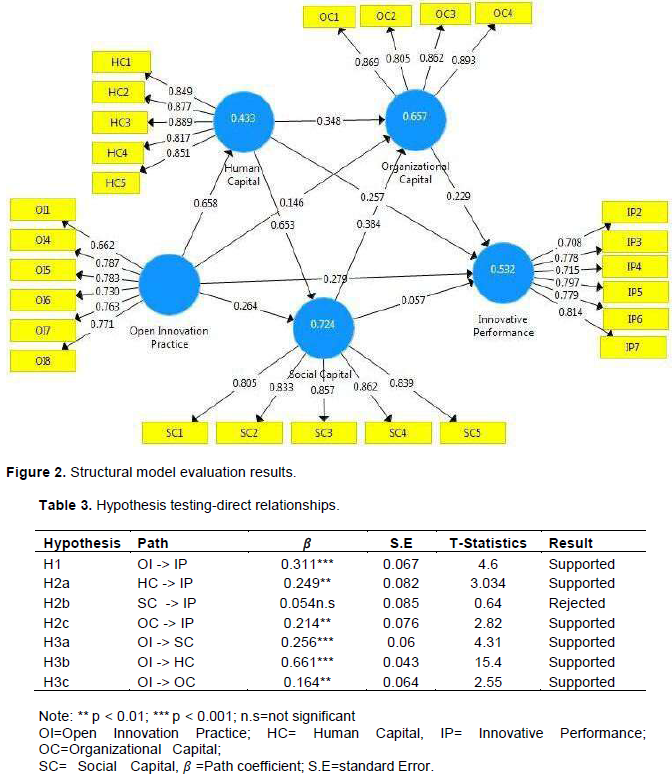

Once the measurement evaluation criteria were fulfilled, the goodness of the theoretical model should exist adamant. Structural model tin can be evaluated using the coefficient of decision (Rii) and the forcefulness of path coefficients (β) derived from bootstrapping techniques (Chin, 2010). Too, as the hypotheses formulated in this research involved arbitration relationships, the significances of the indirect effects were verified by the variance accounted for (VAF) analysis (Pilus et al., 2016). Effigy 2 and Tabular array 3 summarize the results of the terminal model. Table iii summarizes the results of the proposed hypotheses. Appropriately, the OI practice has positive and significant direct influence on both the intellectual majuscule and the innovative functioning, supporting H3a, H3b, H3c, and H1. Moreover, the organizational and homo capitals have a positive and significant direct influence on the innovative functioning, confirming H2a and H2c. But the impact of social capital on the innovative performance is not meaning, rejecting H2. The explanatory power of the model was examined using the coefficient of determination (R2) value (Pilus et al., 2016). Rtwo denotes the extent of variance in the endogenous constructs explained past the exogenous variable/south (Chin, 2010). As depicted in Figure two, the R2 results indicate a robust model with 72% of the variance in the social capital, 66% of the variance in the organizational capital letter, 54% of the variance in the innovative operation and 44% of the variance in the human being capital explained by the independent variable/s.

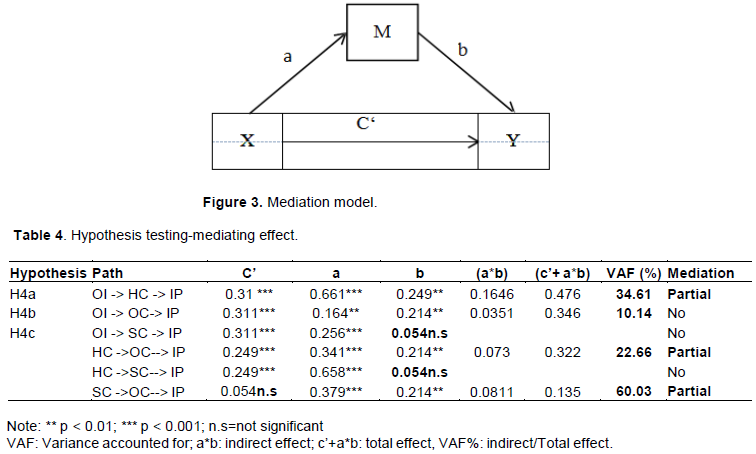

The analysis of arbitration effects

Mediation occurs when causal predecessor X influences the outcome variable Y through intervening variable Thousand (Figure three). The whole issue of X on Y is divided into direct and indirect components. The route from X to Y without passing from M is called straight effect and represented past-c' ‖. The path from X to Y through Thousand is called the indirect consequence. The indirect effect coefficient (a x b) is the product of -a‖ and -b‖. The full effect (C) is hence the aggregating of direct and indirect effects (C=c'+ a 10 b).

The bootstrapping approach was applied to check the mediation effect. The bootstrapping approach does not make any assumptions about the shape of the variables' distribution or sampling distribution of the statistics. Information technology tin be used to small sample sizes with high confidence. The approach is therefore flawlessly fit for the PLS method. Likewise, this approach exhibits college statistical power compared with the Sobel test. As suggested by Pilus et al. (2016), the significance of the private paths (10-M and M-Y) is a requirement for the arbitration status. Moreover, the indirect effect is assessed by the size of its effect relative to the total event (Indirect effect/Total effect) described as variance accounted for (VAF). When the indirect effect is significant but does non blot any of the exogenous latent variable's event on the endogenous variable, the VAF would be less than 20% which implies almost no arbitration. Conversely, when the VAF has relatively large outcomes (above 80%) a full mediation occurs. When the VAF value is between twenty and 80% the situation is characterized every bit fractional mediation. Table 4 shows the bootstrapping results including direct, indirect, total effects and VAF for the paths with the potential mediating factors. Appropriately, as the impact of social capital on innovative capital letter is insignificant, the mediation role of social capital between open innovation practice and innovative operation (H4c) is not supported. The other mediating factors were evaluated with respect to the VAF, as the values of ‗a' and ‗b' are significant. Given the VAF values, the impact of OI practice on the innovative performance is partially mediated by human capital. But the organizational capital has an insignificant office in mediating this effect. Hence H4a is supported but H4b is dropped. Furthermore, the result from Table 4 confirms that the impacts of social and human majuscule on the innovative performance are partially mediated through the organizational capital.

CONCLUSION

This paper examined the link amid OI practise, intellectual upper-case letter, and innovative performance using a sample of 243 manufacturing SMEs operating in Ethiopian. A conceptual model which delineates the relationships was developed and evaluated using the SmartPLS. Empirical results revealed that OI do has a significant and positive outcome on the innovative operation of SMEs, supporting H1 (β=0.311, t = four.60, p<0.001). This implies that SMEs in developing countries may increase their innovative functioning by implementing the open innovation practices. This upshot similar to Hung and Chiang (2010) findings validated the relationship between open up innovation and firms' functioning. The finding reveals that the open innovation practice is a common trend both for large and SMEs in developed and developing countries. It also shows that adopting an open arroyo is worthwhile for companies to improve their innovative performances. The furnishings of open innovation practice on social upper-case letter (H3a: β=0.256, t = four.31, p<0.001), human capital (H3b: β=0.661, t = 15.40, p<0.001) and the organizational capital (H3b: β=0.164, t = 2.55, p<0.001) were besides positive and significant. This result suggests that SMEs in developing countries may enhance their intellectual capital using open innovation practices. These findings illustrated that open innovation practice is critical for SMEs to get technological resources (Lichtenthaler, 2008) and new channels (Lee et al., 2010, Van de Vrande et al., 2009) that enhance the quality and speed of their innovations (Van de Vrande et al., 2009). They also showed that OI practise is critical for them to access new ideas, knowledge, supplementary resources and opportunities from the external environment which could ameliorate the stock of cognition (human, organizational and social upper-case letter) in the company (Laine and Laine, 2012).

Moreover, the impacts of the intellectual capital components on the business firm's innovative functioning were also investigated independently. The results discovered that human capital is positively and significantly associated with innovative performance in SMEs, supporting H2a (β=0.249, t = iii.034, p<0.01). This finding supports the previous result from Zerenler et al. (2008) and Alpkan et al. (2010). In fact, when SMEs are equipped with highly skilled employees they are capable to perform and innovate better. The impact of organizational capital was similarly found to be positively and significantly connected to the innovative performance, supporting H2c (β=0.214, t = ii.82, p<0.01). This implies as the organizational capital of SMEs is enhanced, SMEs create capability to meliorate their products and processes, which further boost their innovative operation. This result is consistent with previous findings that canonical the disquisitional role of organizational majuscule for the innovative performance (Zerenler et al., 2008; Leitner, 2011). But the association between social capital and innovative performance was attested to be insignificant and H2b (β=0.054, t = 0.64, due north.s) was rejected. This outcome contradicts the discoveries of Zerenler et al. (2008) and Hsu and Fang (2009). The impact of social capital letter on the innovative performance was found to be indirectly through the organizational capital. Hence the bear upon of social capital can exist improved through the development of organizational capital. Finally, as presented in Tabular array 4 the relationship between OI practice and innovative functioning is partially mediated by human capital (H4b). In contrast, the mediation role of social capital (H4c) and organizational capital (H4b) are not supported.

The paper has important theoretical and practical contributions. First, previous studies on OI practices and intellectual uppercase were focused primarily on high-tech and large enterprises in avant-garde economies (Lee et al., 2010; Spithoven et al., 2013; Popa et al., 2017). The findings of this newspaper could expand our understanding of the connection among open up innovation exercise, intellectual capital and the innovative functioning from the context of SMEs operating in a developing state, which could also provide good implications to SMEs operating in similar situations. Secondly, the prevailing literature on OI practice yet relies, predominantly on case studies and conceptual frameworks with trivial empirical enquiry in the context of SMEs (Lee et al., 2010; Popa et al., 2017). Therefore, the paper supplements the literature on the effects of open innovation practice on intellectual capital and afterwards on the innovative performance by assessing empirically. This provides additional evidence to elucidate the conclusive results.

Furthermore, the report adds to the body of knowledge on the impact of OI practise on the elements of intellectual capital and the interplay amid the different intellectual capital components. Finally, the paper throws low-cal on the arbitration part of intellectual upper-case letter components on the positive impact of open up innovation do on the innovative performance of SMEs.

From applied perspectives, the findings hold crucial implications for managers. Offset, the result shows that OI practice is a key factor in enhancing the innovative performance in SMEs. The innovative performance in SMEs tin exist considerably improved by pursuing open innovation practise designed to stimulate new thought sharing, knowledge creation, and supply of complementary resources, new marketplace opportunities, and channels. It was also establish that innovative performance needs more intellectual majuscule, indicating that managers should highly emphasize on developing and wisely utilizing the intellectual capital. Specifically, firms should train employees to enrich their work experience and ameliorate homo uppercase, develop a close relationship with their stakeholders to enhance the social capital and design efficient systems to improve structural uppercase. Another key finding is that human capital reinforces the positive effect of open innovation practice on the innovative functioning in SMEs. Hence, equipping employees with the required skill and cognition is a critical issue to increase the consequence of open innovation practise on the innovative operation of SMEs.

Lastly, the findings of this paper are specific to manufacturing SMEs operating in Ethiopia. Generalizing the results to all industry and all sizes of enterprises need further investigations based on both cross-sectional and longitudinal information. In addition, with more openings, the spread of intangible knowledge across firms' boundaries could erode the unique assets of firms and could create challenges in managing the intellectual capital letter. Therefore, it needs further investigation.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The writer has not declared any conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This piece of work was supported past the Mekelle Academy, Ethiopia, under the project grant [CRPO/EITM/PhD/ 001/08]. The author is grateful for the financial support provided.

REFERENCES

| Ahn J, Minshall T, Mortara Fifty (2015). Open innovation: A new classification and its impact on house performance in innovative SMEs. Journal of Innovation Management three(2):33-54. | |

| Alpkan 50, Bulut C, Gunday G, Ulusoy G, Kilic Thousand (2010). Organizational back up for entrepreneurship and its interaction with man capital letter to enhance innovative operation. Management Decision 48(5):732- 755. | |

| Bianchi Yard, Campodall'Orto S, Frattini F, Vercesi P (2010). Enabling open up innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: how to observe culling applications for your technologies. Research and Development Management 40(iv):414-430. | |

| Bigliardi B, Dormio A, Galati F (2012). The adoption of open innovation within the telecommunication industry. European Journal of Innovation Management 15(one):27-54. | |

| Buganza T, Verganti R (2009). Open innovation process to inbound noesis Collaboration with universities in iv leading firms. European Journal of Innovation Direction 12(3):306-325. | |

| Carmona-Lavado A, Cuevas-Rodríguez G, Cabello-Medin C (2010). Social and organizational capital: Edifice the context for innovation. Industrial Marketing Direction 39(ane):681-690. | |

| Chen CJ, Liu TC, Chu MA, Hsiao YC (2014). Intellectual capital and new product development. Journal of Engineering science Technology and Direction 33(i):154-173. | |

| Chesbrough HW (2003). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. | |

| Chin WW (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of partial least squares. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 655-690. | |

| Dahlandera L, Gann D (2010). How open is innovation? Research Policy 39(6):699-709. | |

| Dakhli M, De Clercq D (2004). Human being upper-case letter, social capital, and innovation: A multi-country report. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 16(2):107-128. | |

| Delgado-Verde M, Castro GD, Amores-Salvadó J (2016). Intellectual upper-case letter and radical innovation: Exploring the quadratic effects in technology-based manufacturing firms. Technovation 54(1):35-47. | |

| Fan I, Lee R (2009). A complication framework on the report of knowledge flow, relational capital, and innovation adequacy. Proceedings of the International Conference on Intellectual Capital. pp. 115-123. | |

| Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement fault. Journal of Marketing Research 18(1):39-50. | |

| Freel M (2000). External linkages and product innovation in small manufacturing firms. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 12(1):245-266. | |

| Garcia R, Calantone R (2002). A Critical Look at Technological Innovation Typology and Innovativeness Terminology: a Literature Review. Journal of Product Innovation Management 9(2):110-132. | |

| Gassmann O, Enkel E, Chesbrough H (2010). The future of open innovation. Research and Evolution Management forty(3):213-221. | |

| Gunday G, Ulusoy M, Kilic K, Alpkan L (2011). Effects of innovation types on business firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics 133(2):662-676. | |

| Hailekiros GS, Renyong H, Qian S (2016). Adopting Open Innovation Strategy to Empower SMEs in Developing Countries. International Briefing on Engineering science and Engineering Innovations (ICETI 2016) Atlantis Press pp. 82-87. | |

| Hair Jr JF, Hult GT, Ringle C, Sarstedt Thousand (2016). A primer on partial to the lowest degree squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications. | |

| Colina CW, Jones G (2001). Strategic Management Theory — An Integrated Arroyo. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. | |

| Hsu YH, Fang West (2009). Intellectual capital and new product evolution functioning: The mediating role of organizational learning capability. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 76(one):664-677. | |

| Hung KP, Chiang YH (2010). Open up innovation proclivity, entrepreneurial orientation, and perceived business firm performance. International Journal of Applied science Management 52(three/4):257-274. | |

| Khalique Thousand, Bontis N (2015). Intellectual uppercase in minor and medium enterprises in Islamic republic of pakistan. Journal of Intellectual Capital 16(1):224-238. | |

| Kohl H, Galeitzke 1000, Steinhöfel Eastward, Orth R (2015). Strategic intellectual majuscule management as a driver of organisational innovation. International Journal of Noesis and Learning ten(two):164-181. | |

| Koufteros X, Vonderembse G, Jayaram J (2005). Internal and External Integration for Product Development the Contingency Effects of Uncertainty, Equivocality and Platform Strategy. Determination Scientific discipline 36(1):97-133. | |

| Laine MO, Laine A (2012). Open innovation, intellectual majuscule, and unlike knowledge sources. Republic of finland pp. 239-245. | |

| Laursen K, Salter A (2006). Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation functioning among UK manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Periodical 27(2):131-150. | |

| Lee S, Park G, Yoon B, Park J (2010). Open innovation in SMEs-An intermediated network model. Enquiry Policy 39(i):290-300. | |

| Leiponen A, Helfat C (2010). Innovation objectives, noesis sources, and the benefits of breadth. Strategic Management Periodical 31(2):224-236. | |

| Leitner KH (2011). The event of intellectual capital on product innovativeness in SMEs. International Journal of Engineering Management 53(i):ane-18. | |

| Lichtenthaler U (2008). Open innovation in do: an analysis of strategic approaches to technology transactions. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Direction 55 (1):148-157. | |

| Mention AL (2012). Intellectual capital, innovation, and functioning: A systematic review of the literature. Concern and Economic Research two(1):1-37. | |

| Minshall T, Letizia Thou, Robert V, David P (2010). Making "Asymmetric" Partnerships Work. Inquiry-Engineering Management 53(3):53-63. | |

| Mortara L, Minshall T (2011). How do large multinational companies implement open innovation? Technovation 31(10-11):586-597. | |

| Narula R (2004). R & D collaboration by SMEs: new opportunities and limitations in the face of globalization. Technovation 25(two):153-161. | |

| Parida V, Westerberg Grand, Frishammar J (2012). Inbound Open up Innovation Activities in High-Tech SMEs: The Impact on Innovation Performance. Journal of Small-scale Business Direction 50(two):283-309. | |

| Popa S, Soto-Acosta P, Martinez-Conesa I (2017). Antecedents, moderators, and outcomes of innovation climate and open up innovation: An empirical written report in SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Alter 118(1):134-142. | |

| Shih KH, Chang CJ, Lin B (2010). Assessing noesis creation and intellectual upper-case letter in cyberbanking Industry. Journal of Intellectual Upper-case letter 11(i):74-89. | |

| Spithoven A, Vanhaverbeke W, Roijakkers N (2013). Open up innovation practices in SMEs and large enterprises. Small Business Econnmics 41:537-562. | |

| Subramaniam K, Youndt K (2005). The influence of intellectual uppercase on the types of innovative capabilities. University of Management Periodical 48(1):450-463. | |

| Tovstiga G, Tulugurova E (2007). Intellectual capital letter practices and performance in Russian enterprises. Journal of Intellectual Capital 8(4):695-707. | |

| Užienė L (2015). Open up innovation, cognition flows, and intellectual capital. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 213(i):1057-1062. | |

| Van de Vrande V, De Jong JP, Vanhaverbeke W, De Rochemont One thousand (2009). Open innovationin SMEs:Trends, motives and management challenges. Technovation 29(i):423-437. | |

| Wang Y, Zhou Z (2012). Can open innovation approach be applied past latecomer firms in emerging countries? Journal of Cognition-based Innovation in China iv(three):163-173. | |

| Youndt MA, Subramaniam M, Snell S (2004). Intellectual Capital Profiles: An Examination of Investments and Returns. Periodical of Management Studies 41(2):336-361. | |

| Zerenler M, Hasiloglu S, Sezgin M (2008). Intellectual capital and innovation performance: Empirical evidence in the Turkish automotive supplier. Journal of Technology Management and Innovation 3(4):32-xl. | |

mcconnellineircied.blogspot.com

Source: https://academicjournals.org/journal/AJBM/article-full-text/3680FA959041